Recent Recordings by Area Jazz Artists

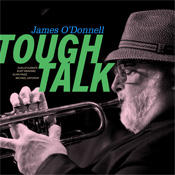

For many in our area, trumpeter James O’Donnell is best known as co-leader with RJ Spangler of the prodigious Planet D Nonet, but he also works in other contexts and can often be heard leading a quintet in various Detroit venues. This combo, made up of some of the area’s finest, has been busy in Ferndale and Ann Arbor studios, resulting in Tough Talk (Eastlawn ELD-043), featuring O’Donnell on trumpet, flugelhorn, maracas, and vocals, Alvin Paige, tenor and baritone saxes, Michael Zaporski, piano, Kurt Krahnke, string and electric bass, and Djallo Djakate, drums, with special guests RJ Spangler, congas, tambourine and cowbell as well as the whole Planet D Nonet on two tracks (arrangements are by Ryan Bills, Jeff Cuny, and the band).

The Quintet is a working band that appeals to a variety of tastes and one of its strengths lies in a judicious choice of tunes to improvise on, and while selected from the middle history of jazz, from the thirties to the sixties, the blowing is very much in the modern mainstream manner. The recital begins with the R&B jazz tune, “Tough Talk,” from the 1963 Jazz Crusaders album by the same name. Djakate drives the music with a powerful boogaloo beat as the leader and pianist Zaporski solo in a funky expansive manner. The spirit continues with Steve Wonder’s “All in Love is Fair,” with nice backbeat and tasteful electric bass backing, introducing, after a brief trumpet outing, Paige’s swaggering yet concise tenor sax solo. Things take a different turn with “Tulip or Turnip” from the forties, with O’Donnell putting down his horn to sing, accompanied by the whole Planet D Nonet. It seems that the Planet crew cannot get away from their fascination with Duke Ellington here, but who can blame them; indeed, this CD also includes Duke’s classic “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” and the rarely heard “Azalea” first recorded at his meeting with Louis Armstrong in 1961 in a combo setting, but here backed by the whole Nonet. The latter features O’Donnell fooling around with a Satchmo-like vocal as a tribute to the master. The boogaloo returns with “Mean Greens,” the title tune from another soul jazz classic by Eddie Harris, with Paige once again impressing with a rapid-fire hard driving tenor solo, followed by an equally compelling brief one by O’Donnell. The leader then takes us back in time to 1930 with “I Want a Little Girl,” first recorded by McKinney’s Cotton Pickers in 1930, and played and recorded by many since then, apparently chosen here by the leader as homage to his teacher and mentor, trumpeter Russell Green, who played it at every performance. This version is more hard swinging than most and serves as a vehicle for O’Donnell and Zaporski to impressively strut the more bluesy side of their work. Variety reigns on as the Quintet moves on Neal Creque’s infectious Latin-inflected “Dracula,” from a 1970 Grant Green album, here prominently driven by Spangler’s percussion mastery. A slower Latin tune, Clare Fisher’s enchanting cha-cha “Morning,” ends the recital with a final chord on the piano.

The heterogeneous selection of tunes and rhythms on this CD is bound together by a stylistic unity, by the highly personal soloing of all involved, and by a tight propulsive rhythm section. Much of the success must be attributed to the arrangements by Ryan Bills, and on one tune by Jeff Cuny (“Azalea”), as they create contexts for the soloists, providing imaginative ensemble passages that interrupt the progression of simple head, blowing, then head again order so often encountered in modern jazz. O’Donnell here steps out in style, demonstrating his instrumental prowess that incorporates the best elements of the jazz trumpet tradition, using a wide variety of instrumental techniques, including mutes, in a highly personal, emotionally honest style.

To conclude, a word about saxophonist Alvin Page, the only member of the Quintet who may not be familiar to many followers of the Detroit jazz scene, but who fits in perfectly with these seasoned professionals. He hails from San Diego, where he began learning jazz with Detroit’s own Charles McPherson and is currently finishing his studies at Michigan State. His tenor sax playing on this CD is exemplary: he knows how to tell emotionally charged succinct stories, fitting perfectly into the sound palate of each arrangement with no wasted notes. Most important, he is just as adept on the baritone sax, with his own sound and approach, expertly demonstrated on “Dracula.”

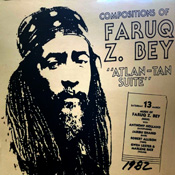

In the seventies and eighties of the last century, saxophonist, composer, and poet Faruq Z. Bey (1942–2012), a man of strong personality, was a catalyst for many of the more audacious artistic developments in Detroit’s African American community. Many of his prodigious musical and poetic adventures now live only in the memories and autobiographies of his contemporaries, but he is well remembered for the various incarnations of the group Griot Galaxy, documented only by two recordings, Kins (1982), and Opus Krampus (1985) but also by Live at the D.I.A. (1983), a double CD released in 2003 on Entropy Stereo. The label, produced by musician Mike Khoury, has tirelessly documented marvelous music of great artistic and historical importance, and was instrumental in helping Bey return to performing after a decade of obscurity following an extremely serious motorcycle accident. When the saxophonist was finally able to play again, much of his latter-day work was released on Entropy. And now Khoury has done it again, putting out a hitherto unknown Bey recital from 1982 recorded by Ron DeCorte, who had worked on Kins and the D.I.A. album; indeed, this one was also recorded during a performance at the Detroit Institute of Arts a year earlier. The Atlan-Tan Suite features Faruq Z. Bey and Anthony Holland, saxophones, Robert Allison, vibraphone, Marlene Rice and Gwen Laster, violin, and Jaribu Shahid, bass and cello, with all compositions by the leader.

Just a glance at the personnel reveals the unique qualities of this work. Shifting driving rhythms were such an elemental factor on Bey’s music and Tani Tabbal’s drumming style, locked in perfectly with Jaribu Shahid’s bass, was such an immediately recognizable emblematic element in Griot Galaxy’s sound signature that the lack of a drummer is striking. The presence of a vibraphone and a pair of violins are likewise unexpected as the remaining musicians were all stalwarts of Griot Galaxy. It is therefore interesting to discover, upon listening, that while definitely singular, this is more a riff on Bey’s other work at the time than a radically unusual recital. Two of his compositions, “Liberty Street Rundown” and “Kins,” are also documented elsewhere and the arrangements are not that different, with accommodations made for the lack of a drummer. A third track, “Ink,” could easily have been an adaptation of a tune played by Galaxy, but the opening suite seems to take more advantage of the novel instrumentation, with fascinating writing (the third and fourth movements belong to his “Z-Series” and a version is found opening the D.I.A album).

The Atlan-Tan Suite is no mere curio but a genuine historical find. The lack of drums in no way impedes rhythmic propulsion; indeed, it not only puts more spotlight on the precise and creative aspects of Shahid’s big-toned bass but also seems to inspire the others to loosen up their ensemble and solo work. Allison’s vibes add a welcome new sonority and his soloing fits right in with the more familiar players. Violinists Marlene Rice and Gwen Laster have since then moved on to New York where they have developed illustrious careers (they have both been back in the area in recent times at Ann Arbor’s Edgefest), and it is interesting to hear them solo with imagination in this context. The saxophonists solo with power and ingenuity, sometimes seemingly with even more abandon than on the other versions of some of the tunes. Although this is not noted on the cover, one assumes that Bey was on tenor and alto while Holland played the alto and soprano. Both seem to have been in top form that night, but to this listener it is Holland’s singular soprano sound that left the most powerful impression, his solos full of imaginative melodic invention, emotive creativity, and technical perfection.

Bey was a performer of singular presence and exuberance of a kind that is difficult to capture on tape, but concert recordings such as this one come as close to relaying his deeply personal approach to life and art as one could want. This recital deserves focused, repeated listening to both the larger structural elements and the fleeting movement of individual creativity by a group of magnificent musicians, most of whom are still actively playing today. This is one to get and keep.