Recent Recordings by Area Artists

This month’s offerings cover much of jazz history, once again documenting the wide stylistic range of Detroit-area musical artists, albeit all by members of the diaspora, who have fanned out throughout the land.

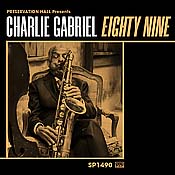

We begin with a lovely surprise: a recording by saxophonist, clarinetist, and vocalist Charlie Gabriel. New Orleans-born and the fourth generation of local musicians, he spent sixty-three years in Detroit before returning to his native city, where he has been very present and active, most prominently as a member of the Preservation Hall Jazz Band. The Crescent City’s gain was certainly our loss, as Gabriel was one of the most versatile and beloved players on our scene, often in the company of J. C. Heard, Marcus Belgrave, and other masters. His new recording, a gem of mainstream jazz, is entitled simply Eighty-Nine (Sub Pop SP 1490), and the title is self-explanatory. Accompanied only by guitarist Joshua Starkman and on most tracks by bassist Ben Jaffe, Gabriel laid down six jazz standards and two of his own tunes.

The beginning is pensive with a touch of melancholy on “Memories of You,” as Gabriel was still mourning the loss of his brother Leonard, who was laid low by Covid. From the start, the New Orleans style mastery of the clarinet is right there, rich toned, with just a slight edge, warm and expressive; all harmonically and melodically timeless. Gabriel can play second line as well as bebop and the connections are seamless in service to expression. He moves on to the tenor sax for a passionate exploration of Strayhorn’s “Chelsea Bridge” (apparently inspired by a Turner painting of a different bridge over the Thames), and then returns to the clarinet for “I’m Confessing that I Love,” but here comes a surprise: a relaxed, warm-voiced vocal by the horn man. Like so many jazz players of his generation, including his old friend and companion Belgrave, Gabriel sings very much as he plays, and it is a delight (his vocals are also featured on two other songs). His final clarinet feature here is on “Stardust.” There have been countless recordings of the song since Hoagy Carmichael wrote it almost a century ago; as far as the clarinet is concerned the most famous version is probably the one laid down by Artie Shaw, but to me Gabriel’s is definitive. Like throughout the album, he seems to have distilled down the essence of these songs as he has explored them over decades. This is a recording that one will return to again and again.

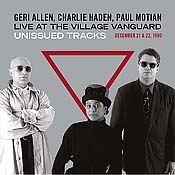

Unlike Gabriel, who came here when he was eleven years old, Geri Allen was born and raised in Detroit, attending Cass Technical High School, mentored by Marcus Belgrave and many others. Her early passing was a shock to all, as she seemed to be going from pinnacle to pinnacle in her artistic trail. Having mentored many students at the University of Michigan, she had moved on to her alma mater the University of Pittsburgh, where she had inherited the chair held by her professor Nathan Davis. Allen, like her mentor Belgrave, was engrossed in the whole history of jazz, loving everyone from Mary Lou Williams to Ornette Coleman, with whom she made a fine album. Among her numerous trios, a collaboration with bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Paul Motian resulted in one of her finest albums, the collaborative 1987 Etudes, that included a particularly fine rendition of Coleman’s “Lonely Woman,” originally recorded with Haden, who contributed a marvelous solo to the new version. A club performance of the same trio from three years later was released in Japan as Live at the Village Vanguard. It was a mixed affair; many of the tunes were somewhat subdued, and as good as these magnificent artists were, it did not seem to live up to what they were able to achieve in their studio recording. Now, over three decades after the Vanguard gig, we get Live at the Village Vanguard: Unissued Tracks December 21 & 22 1990 (Somethin’ Cool SCOL 4029), issued in Japan, available on various streaming platforms. In most cases one expects such rejects to be of secondary value for completists, but in this case the reverse seems to be the case. To my ears, this collection is superior to the original release. From the beginning “Bouncing with Bud” you get more of a sense of what it was like to be there, with more passion and spirit in the interaction between the three. It seems as of all the up-tempo tunes were held back and are now available here, but these shed light on the way the three members of the collaborative trio worked together. The midtempo “Dancing in the Dark” is particularly seductive, with a laid-back tempo that allows Allen to develop a long series of exemplary choruses, with just hints of her Monkish affection. Motian and she share the announcements; the last track begins with her voice, lending a bittersweet element reminding us of what was lost. These are not leftovers but an essential part of Allen’s legacy, although one should keep in mind that this was a collaborative trio with Holland and Motian in suitably masterful form.

In the seventies of the last century Detroit was one of the prime centers of the new kinds of jazz that were challenging post-bop orthodoxy. One of the most dynamic players who grew up in that era is saxophonist Skeeter Shelton. His father Adjaramu Shelton was a professional drummer who played with Gene Ammons and other mainstream players, mostly in Chicago. Shelton has been at the forefront of the local avant scene for decades, playing in Hakim Jami’s Street Band, in different groups by the side of Farouk Z Bey, including Griot Galaxy, and in configurations with Anthony Holland, often leading his own groups. By chance he played a duet with Chicago drum master Hamid Drake, who, it turned out, had studied as a young man with his father. The collaboration was so successful that the two rejoined once again in 2019 in Detroit to record Sclupperbep (Two Rooms TR-006).

The set begins with the rousing “We Must Play Music for the Children,” composed by Skeeter’s father, which segues briefly into his own “Attic,” a contrasting slow pensive tune. Right away we recognize the signature aspects of both musicians: Shelton’s most powerful, singing, expressive tenor sax tone with its characteristic vibrato, and his deliberate repetitions and development of melodic elements, coupled with Drake’s dancing rhythms that dart in and out from direct support to contrasting patterns, in full partnership rather than as basic accompaniment. On “Forest Dancer,” the mood shifts to a more meditative vibe, introduced by bells and pan pipe; Shelton shifts to tenor and the spirit begins to move, slowly evolving into halfway into an intense late-Coltrane style exploration, with virtuosic saxophone playing in perfect lock with penetrating polyrhythmic percussion. The next track, “Charles Miles,” opens with Shelton alone in different mood, playing softer, more traditional, bluesy phrases, eventually joined by Drake, paying their dues to the roots of the music. The recital ends with “Now That I’m Free,” a slow prayer walk through a highly spiritual landscape, ending with a nod to Trane’s “A Love Supreme.”

The trio of Jason Stein, bass clarinet, Damon Smith, double bass, and Adam Shead on drums and percussion has just released Volumes & Surfaces (Balance Point Acoustics bpaltd16016). Stein and Shead belong to two different generations of former University of Michigan music students who have moved on to enliven the Chicago improv scene. The two play together often, frequently in a duo setting, but here they are joined by visiting master bassist Damon Smith, but they blend so well, you would think the trio was a regular band. The most forward element here is Stein’s unique bass clarinet sound, hard edged, but capable of an infinite variety of timbral shadings, equally in command of the multi-octave range of the instrument; Smith likewise utilizes a broad range of bass techniques, arco, pizzicato, percussive, sometimes sounding like a whole string section, while Shead exploits the full range of percussive and timbral potential of his kit, imbuing his rhythms with melodic sophistication that echo his strong compositional talents. Together, they can cry, scream, or laugh, exploiting moods and rhythms together and then intuitively shifting together to new ground. The five tracks, recorded in concert performances, explore different improvisational areas and the three are masters of a wide range of instrumental and improvisational techniques, allowing them to maintain the elements of surprise that are so fundamental to this kind of music.